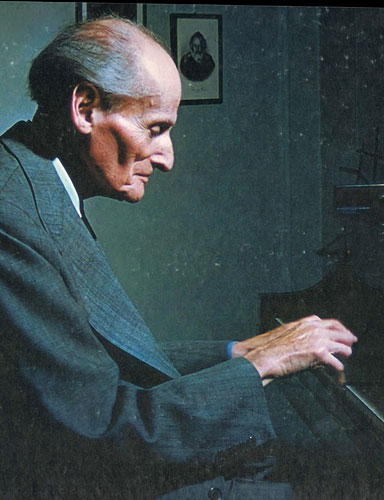

Carl Friedberg

Carl Rudolf Hermann Friedberg (1872 - 1955) was a German pianist and teacher, who after studying piano with James Kwast and with Clara Schumann at the Hoch Conservatory, Frankfurt, later became a teacher there. He then went on to teach at the Cologne Conservatory for 10 years and for 23 years (until his retirement in 1946) at the Juilliard School of Music, which at that time was called the New York Institute of Musical Art. His pupils include William Browning, Malcolm Frager, Bruce Hungerford, William Masselos, and Elly Ney.

Friedberg began what would begin a 60+ year performance career with his official debut on December 2, 1900 with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra under Mahler, having previously performed an all-Brahms recital in the presence of the composer six years earlier.

FRIEDBERG AND BRAHMS

After his early contacts with Brahms through Clara Schumann, Friedberg's next major encounter with the great composer was on the occasion of Friedberg's performing what may have been the first all Brahms piano recital ever given. Friedberg described that event in an unpublished transcript of a taped interview with his student Bruce Hungerford:

"I saw him when I first came to Vienna; he came to my Brahms recital, the Brahms evening [November 7, 1893]. I did not know that he had attended the concert, or I would have died of fright. I played the F Sharp Minor Sonata; two books of the Paganini Variations, four of the Eight Piano Pieces, Opus 76; the Six Piano Pieces, Opus 118; the Two Rhapsodies, Opus 79; and some of the Waltzes. But not the Handel Variations; I have never been so fond of them as the Variations on an Original Theme. I liked those much better. He came back after the recital and invited me to the Tonkunstler Verein for a celebration that night of Ignaz Brull's birthday [Viennese pianist-composer and close friend of Brahms]. And we sat there and celebrated the occasion with food and drink. Then [Brahms] took me to the Imperial Coffee House - he never wanted to go to bed early - and he didn't say one word about my recital until three o'clock in the morning. Then he stroked his beard and said 'You know you played very wonderfully, young man, but you mustn't do that again. You mustn't play a whole evening of Brahms. People don't like that; they don't want me. I am not yet popular enough. Play other things and only one work of mine - you do me a better service.' The humility of that, to say he wasn't popular enough - that they would not like to hear only Brahms! And I had received great applause; I said the applause is due to you, Mr. Brahms, not to me.'

On another occasion, Friedberg asked Brahms to show him the way he interpreted his works for piano, to which he answered grumpily, "I don't give piano lessons'. He relented, however, and, according to Julia Smith, "said to the young man: 'Come home with me and I will show you what I mean concerning certain phrasings, tempi, and personal interpretations of my work.' And through the early dawn, the two walked to Brahms's house. Here the composer made coffee, opened a bottle of his special cognac, and after they had refreshed themselves, seated himself at the piano and musically clarified his spoken thoughts of the earlier evening hours.

"During several subsequent visits Brahms played all of his piano compositions for young Friedberg with the exception of the Paganini Variations. 'His dexterity was not equal to that difficult work anymore,' recalled the eminent pianist. 'He paused only now and then to pick up a pencil to jot down new and more definitive marks of expression than the published editions indicated. He took pains to explain certain intricacies, to interpret different readings.' "

Throughout his career Friedberg was particularly known for his interpretation of Brahms's music. In a review of a performance of the B-flat Concerto with the New York Philharmonic and Bruno Walter in 1933, Olin Downes described Friedberg's special empathy with the Brahms style which came, of course, from his having absorbed the traditions of the period but also from his close association with the composer:

Mr. Friedberg played the formidable part of the Brahms concerto with admirable breadth and energy, which if anything out-Brahmsed Brahms. It is, however, probable that Brahms himself played the B-flat concerto that way - immense paws full of notes, immense breadth and fire, and the piano a second orchestra. Mr. Friedberg's vigorous rhythms and attacks had their due contrast in the treatment of the lyrical phrases. All details contributed to the sensation of the grandeur of great spaces. This was maintained in the 'demoniac' scherzo, but the slow movement was playing of another kind, playing which matched the poetry of the musical thought. In short, it was a performance by a pianist who knew the grand manner and whose traditions are particularly of the period that saw the culmination of Brahms's creative career.

FRlEDBERG'S SINGING TONE

The essence of Carl Friedberg's playing was his "singing tone" and "singing approach" to the piano. In 1884 Julius Stockhausen, the great singing teacher in Frankfurt who numbered among his pupils some of the best-known European singers of that day, was in need of a studio accompanist and coach. Having observed that Friedberg was an excellent ensemble player, who read easily at sight even the most difficult music, including orchestral scores, and who transposed readily into all keys, Stockhausen offered him the position, which was eagerly accepted. Thus while still in his formative years, he had the good fortune to work not only with Stockhausen, but also with other artists, such as Anton Sistermanns, who introduced the Schumann Lieder to the public. Just as he phrased or breathed along with the singer in order to achieve perfection in ensemble, mood, and expression, in the same manner he prepared every phrase of his piano solo works with the same inhalation, often humming to himself to carry the phrase-line naturally. From this early date the singing approach to instrumental music, which was to become one of the prime characteristics of Carl Friedberg's interpretative style, became his ideal. Friedberg gave his own explanation for it in an interview conducted by Harriette Brower which first appeared in the January 2, 1915 issue of Musical America:

I believe the legato touch is of the utmost importance in piano playing; it is the sine quo non of beautiful tone. I am aware that some modern players do not agree with this: they think everything should be played with the arm. Even Busoni, whom I admire exceedingly and consider one of the very greatest artists, says in his edition of Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier that there is no legato possible on the piano. I must differ from those who hold to this idea, for l emphatically believe and can prove there is a legato on the piano; it is the foundation of beautiful tone.

The tone an artist draws from his instrument should be round, full and expressive, capable of being shaded and varied, just as is the bel canto of the singer. We should learn to sing with our fingers.

I endeavor to give my piano tone the quality of the singing voice. For this reason l have made myself familiar with a large number of operas of every school.

Together with much concert work, l have done a great deal of teaching. The student concentrates his efforts on legato touch and on beautiful and expressive tone quality. If I have a melody to play l can do it, as many modern artists do, with a movement of hand and arm for each note that is to say, detaching one note from another. With proper pedaling, such a manner of playing can be made to sound very well. [However] I prefer the pure legato to the detached way of playing.

I believe in making everything musical, in always making the tone beautiful, even in technical exercises and scales. The piano is more than a thing of metal and wood; it can speak, and the true artist will draw from it wonderful tones. It should be part of his constant study to create beautiful tone. I believe a single tone can be made expressive.

In addition to working with singers, Friedberg also studied the violin early in his career. His purpose was not to become a violinist but to learn more about how a singing tone is actually produced on the violin and whether that same tone could be produced on the piano. In teaching his classes, Friedberg made the class listen to the music as he played. He would indicate how he thought the breathing should be done. Then he would make the pupils get up and do the breathing along with the musical line to instill in them the importance of a singing interpretation, even in instrumental music.

NOTE: The preceding text was excerpted from the following source: International Piano Archives at Maryland. Master Pianist: The Artistry of Carl Friedberg. University of Maryland. 1985. Transcript.